Fair warning, this post became a lot longer and more involved than I intended. Proceed at your own risk.

In class, we discussed cultural genre as a potential equivalent to biological classes. Of course, the conclusion we came to was that they truly aren’t equivalent — but is there a way to form a classification of video games similar to how we classify animals?

History of Animal Classification

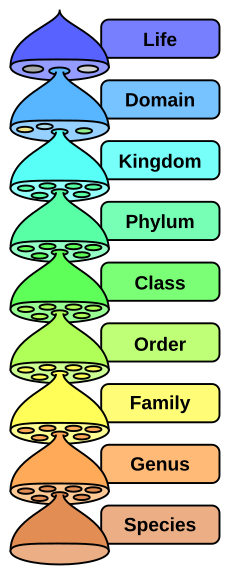

As we can see, the classification of animals starts off very, very broad, with the first step being life. The domain refers to what type of cellular structure an organism has. Animals are actually only found in the third level, kingdom (i.e. the animal kingdom), where plants and fungi break off. From there, we narrow down the type of animal based on more and more specific traits, until finally reaching species. Though this isn’t shown on this particular graphic, we know that there is one more step. Within the species, there are individuals.

Here’s where we run into a problem with our comparison of genre and biological classifications. Our concept of a video game’s “genre” is much too broad, and encompasses too many specifics, as well as too many different kinds of specifics. For instance, arcade games and science fiction (sci-fi) games are considered to be two different genres, despite the fact that they describe entirely different features and can easily overlap. I will only be considering ludic genres, not narrative genres, meaning I am only taking into account the function of a game instead of the story it tries to tell.

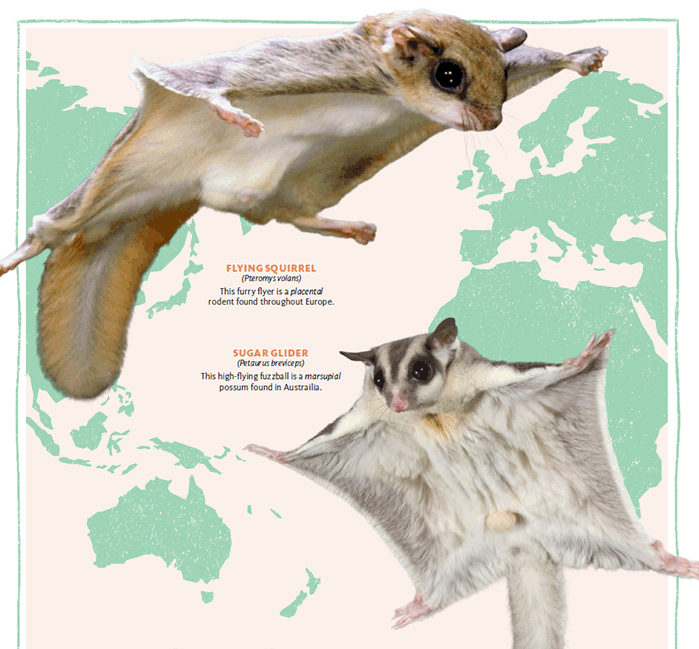

Another issue is the fact that biological classifications are based on what an animal evolved from, not necessarily just what features they have. Convergent evolution is the notion that two animals that come from two different ancestral lines can end up looking and acting very similar due to facing similar evolutionary pressures.

So in order to classify video games in the same way we classify animals, we have to create a gradually-narrowing set of rules, and we have to take into account where or how these games originated.

That’s a lot to consider right off the bat, though, so let’s start with the easiest possible assignments.

Process of Classification

First, we have to consider the least specific features of a video game, before it becomes a video game.

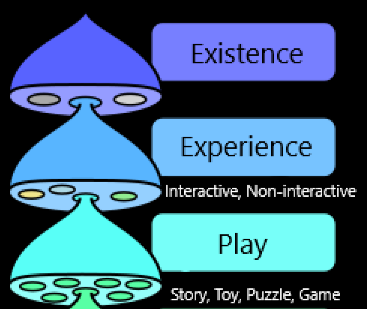

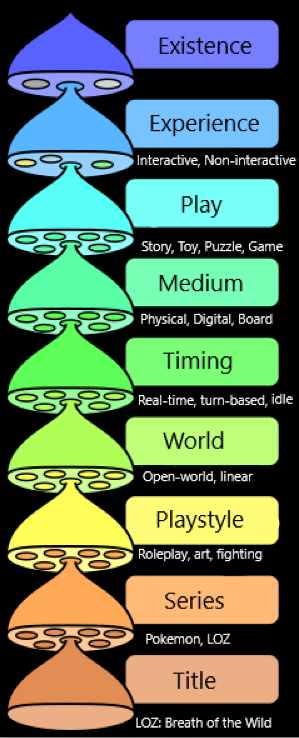

Instead of life, a game must first have existence. After that, it must be an interactive experience. Finally, games diverge from other types of play.

After that, games diverge into different types of mediums. In this post, I’m defining those mediums as physical games (such as sports or tag), board games (such as chess or Monopoly), and digital games (aka video games).

We’ve finally reached the broad definition of what a video game is, but how do we organize video games further? We could divide video games by what platform they’re available on, such as PC, console, handheld, or mobile. But nowadays, many video games exist on many different platforms. So, in this extended metaphor, a game’s platform is closer to an animal’s biome or environment; it isn’t part of the animal’s lineage, but it does define where that animal can survive.

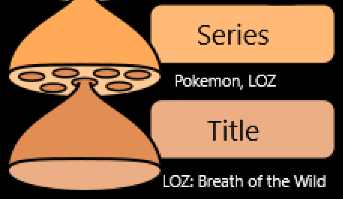

That question stumped me for a bit, so instead, I went all the way down to the opposite end of the chart. What are the most specific units of video games? That would be its title, which in this case, stands for species. Encompassing that is the series or franchise that each game belongs to, acting as the game’s genus.

Now, what comes above series? Some might say the game studio, or the company that developed that video game. However, we run into a similar issue as with platforms. Many companies collaborate in order to make video games, and sometimes games that begin with one company are transferred to another when they are sold or reach an advanced stage of development. Instead, I equate a video game’s game studio to an animal’s evolutionary pressures. Animals may evolve differently based on what resources exist and what competition they face for those resources. Similarly, video games will have certain features depending on the game studio’s budget, expertise, and other current projects.

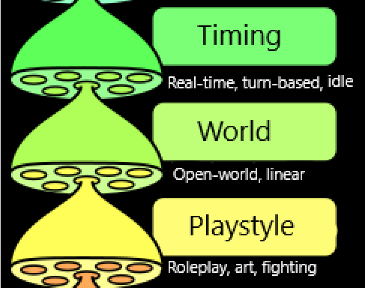

After overthinking this too much in ways that are difficult to put into words, here’s what I settled on:

While we cannot say, for instance, that roleplay games only exist under the umbrella of linear games, we do know that open-world roleplay games and linear-world roleplay games have very different programming and development, regardless of any aesthetic or narrative similarities.

In the end, here’s my final chart of video game classification:

It is certainly not exhaustive, nor entirely conclusive. There are many arguments to be made for reordering timing, world, and playstyle, or phrasing them in different ways, and I would love to hear them. But it is, in my opinion, a step towards a much narrower and more specific way of thinking about ludic genre in video games.

I love this idea. Of course, it has a couple standout flaws to me, to me, the one that stood out first and foremost was the presence of series as a lower level of classification. Though I can see the logic in this, you very quickly run into the issue that for this classification system to work, all games in a series have to share all higher classification levels of genre, which is quite frequently untrue. In fact, even with only the two examples you gave, you already run into some very clear counterexamples. For LoZ, you can’t place all games in the same world style, with both the original and BotW being open world and the others being linear. In Pokémon, there’s substantial difference in timing from the turn based gameplay of Pokémon Gen I-VII and the real time capture mechanics of Pokémon Go or Let’s Go Pikachu/Eevee. And these are pretty tame examples, since if you look to the right series, different titles might not even share the same medium, play, or even experience (look at any adaptation of a ttrpg for series breaking the medium divide, or at any series that has novels that tie its entries together and expand upon the world, which wouldn’t be in the same experience category)

In fact, because titles have the potential to vary so heavily within a single series, if you truly want to create a system that narrows like the biological model of classification, I feel that it’s better to just not consider series in the first place. Graphical style might be a worthwhile addition if you want to stick to 9 levels of classification. If it were added, I would personally place it above the three we typically think of as genre, and have those ordered as world>timing>playstyle. The reason being that graphic style and world type are the two that in my mind have the greatest scale of time between the development of new classifications within them, as they’re both heavily limited in scope by current hardware. Timing and playstyle in my mind could be changed, as they’re both based more on creativity than hardware. Graphic style is only above world because I wanted to group world with the other two, since they contribute more heavily to current genre classifications than graphic style, but I could see world being even higher, since new developments in world progression might be less frequent than new art styles.