Geoff Kaufman and Mary Flanagan’s 2015 paper, “A Psychologically “Embedded” Approach to Designing Games for Prosocial Causes,” presents a compelling argument for the intermixing and obfuscation of serious game topics into games, rather than outright presenting them. In doing so, players pick up and hold on to the messages to a much greater degree. These methods are effective, in part, due to the fact that people feel the need to come to their own conclusions through interpretation, often getting defensive when others try to lead them to the same conclusion. Although these studies were conducted on high school students in regards to prejudice, I would argue that this result could be translated onto younger children in regards to learning games.

While playing through Shape Invasion on Fun Brain, I was immediately struck by how test-like it seemed to be. In other words, there wasn’t much “game” to the game. Regardless of the age group it was targeting, it was repetitive and not very much fun. The educational goal of the game, to teach children about shape identification and spatial relation, was in no way hidden. This clinical approach to learning through games may discourage the child from playing it more than just a couple times. As a kid, my parents made me play Brain Age for the Nintendo DS for at least 15 mins before I was allowed to move on to actually fun games. As a result, I strongly disliked it. If other kids feel similarly, it’s not too hard to imagine them refusing to play these types of games after they realize what they’re attempting to do.

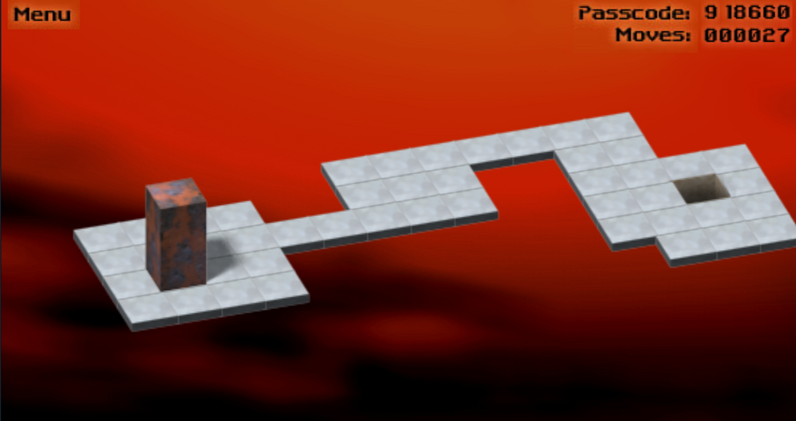

Instead of taking this approach to educational games, Cool Math Game’s Bloxorz utilizes a more embedded technique. The game also intends to teach kids about spacial relation and manipulation skills, but does so while having much more compelling mechanics. The player must navigate a rectangular prism along a level’s varied terrain by manipulating it to cross bridges, hit switches and more while landing it in a square slot at the end of the level. It doesn’t feel like the game forces the player to learn these things directly, but rather seems like a full on game where the motivation is to proceed in the least turns possible. Kids would almost certainly enjoy this as a game, while still learning the intended techniques through a more convoluted method.

This example is quite basic and barely scratches the surface of what educational games for young children could become. However, it does seem to me that the methods of Kaufman and Flanagan could be applied to educational games to get a similar result. By hiding the true educational intent of the game behind engaging mechanics, children may be able to actually have fun while learning.

Work Cited:

Kaufman, G., & Flanagan, M. (2015). A psychologically “embedded” approach to designing games for prosocial causes. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 9(3), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2015-3-5