Cosmology of Kyoto was developed in 1994 by Softedge and published by Yano Electric. Set in the city of Kyoto in 1000 AD during the Heian period, it is a game about the history of Kyoto, Buddhism, and ancient Japanese mythologies. Although the game has a simple point-and-click system and does not have a lot of interactivity, this game is many genres at once and avant-garde for its time in many different ways. Some genres of this game include: open world, adventure, exploration, educational, art, horror, visual novel, slow etc. While the game does many things successfully and there’s so many things to talk about, I will only be focusing on a few aspects of the game due to the limited length of this post.

Cosmology of Kyoto initially sparked my interest for its shocking similarity to one of my favorite artgames, The Great Adventure of Material World by Chinese artist Lu Yang. In this game, you play a blue-haired avatar who travels through the six realms of reincarnation in Buddhism. I loved the philosophical undertone of the game and the way the game viewed life and death through the lens of Buddhism. I also loved the aesthetic style of the game–a combination of modern ACG aesthetic with traditional Asian architecture and art style. When I came across Cosmology of Kyoto, I realized that this is also a game about reincarnation, and it also has a combo of modern and traditional aesthetics–developed 25 years before Lu Yang’s game.

GAMEPLAY & BUDDHISM

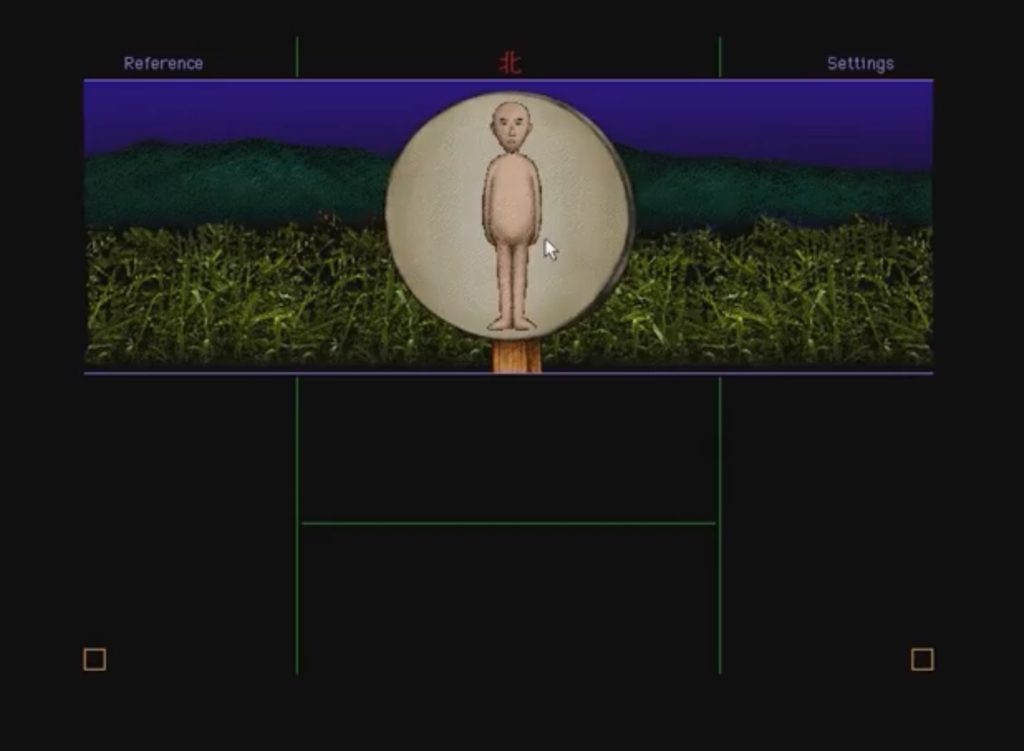

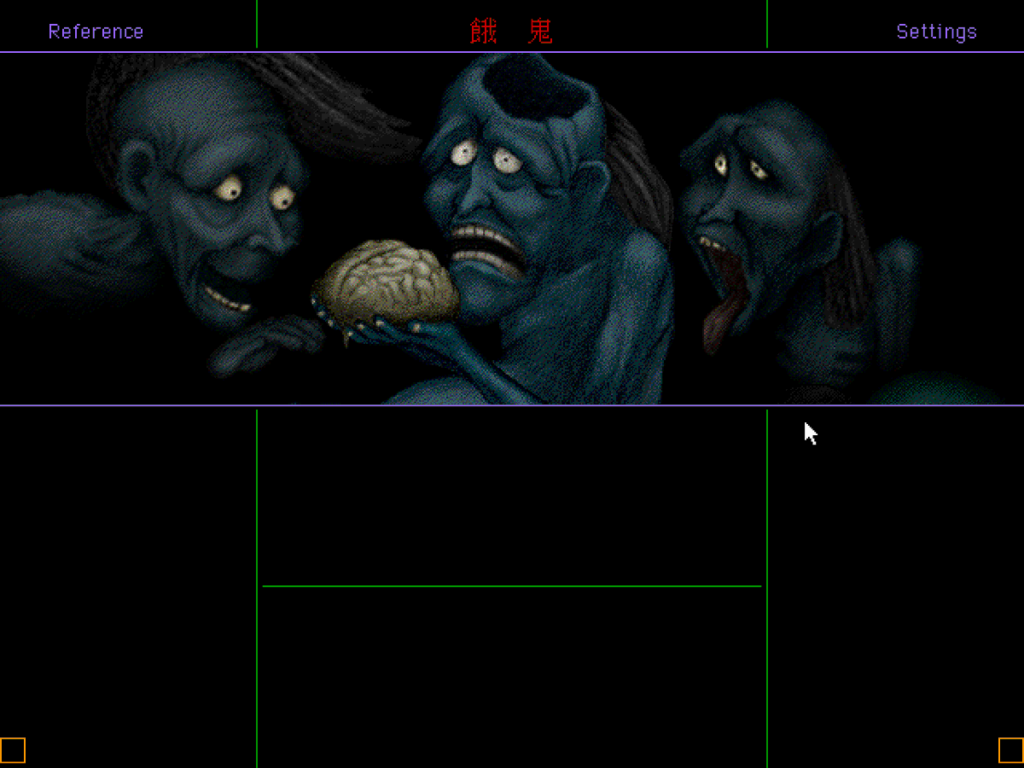

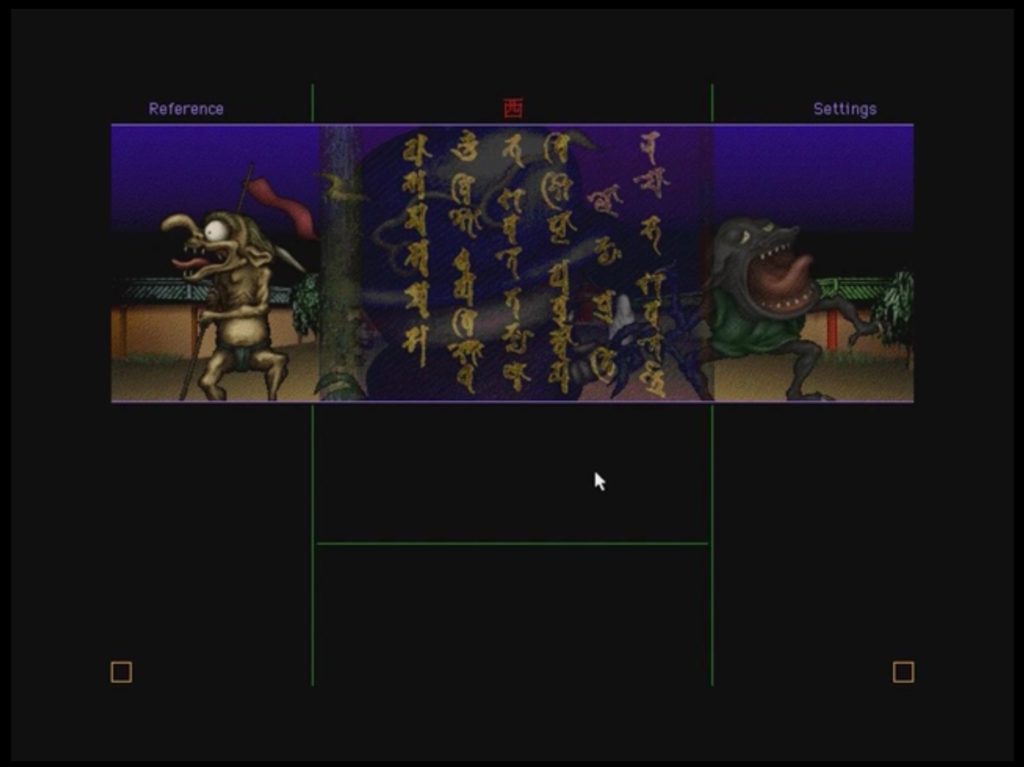

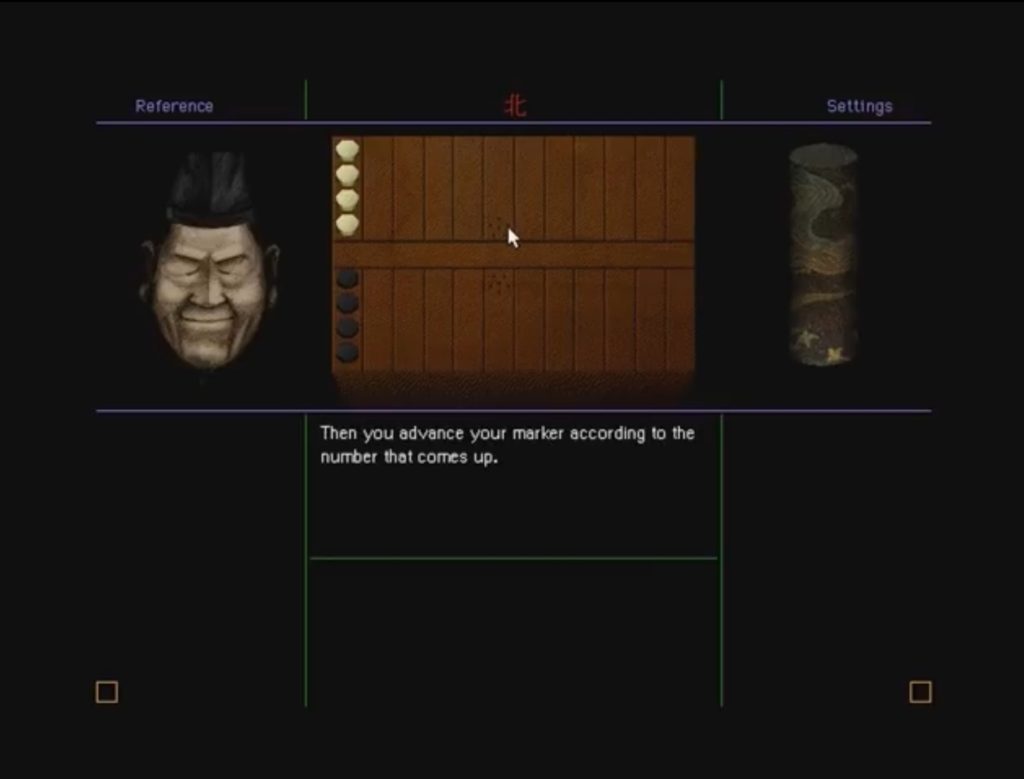

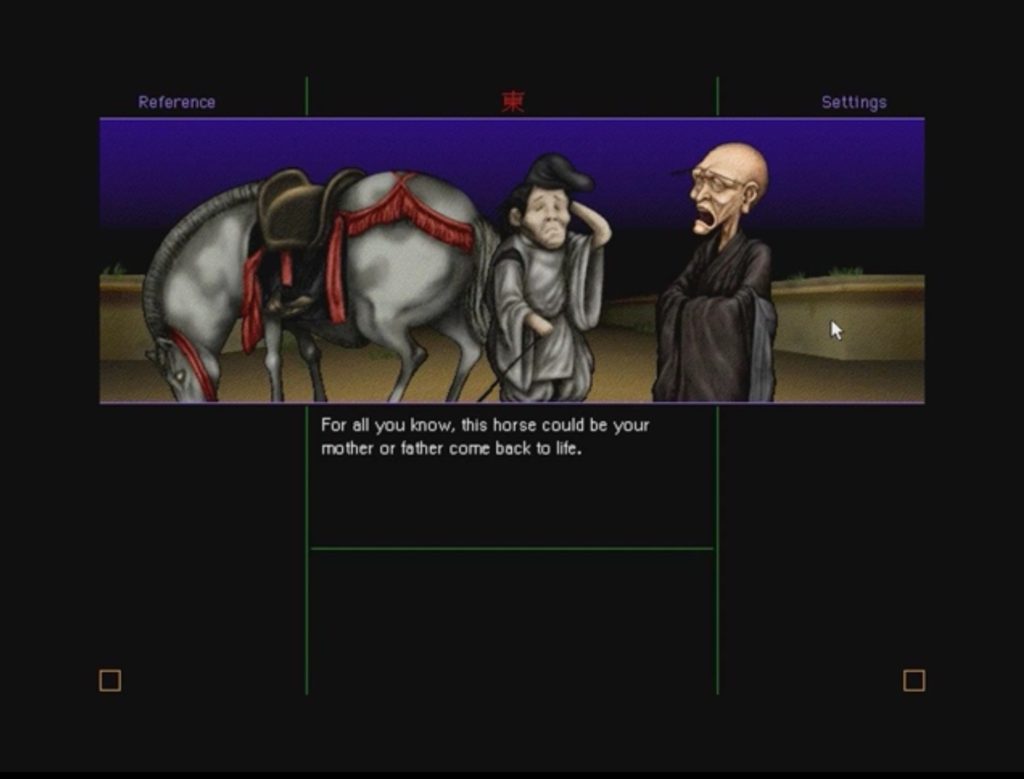

So let’s begin with the experiences of reincarnation in this game. When you first enter the game, you see a mirror in the widescreen display. You click on the mirror to grab it, and see the reflection of your naked human body. You then get dressed and enter the city of Kyoto. You are not given any particular objectives, but have the freedom to explore the city at your own pace. It is extremely easy to die, but death does not mean gameover in Cosmology of Kyoto. Throughout the game, you die a lot and reincarnate into the different realms of reincarnation. There are six realms of reincarnation in Buddhism: hell, hungry ghosts, animals, humanity, ashura, heaven. Usually you reincarnate into hell, where there are demons doing gruesome things, but you get to experience all six realms except heaven throughout the game. Throughout the game, you get to click on objects to collect and apply them. There are also instances when you engage in conversation with a character and get to type your answer. However, ultimately none of these objects or answers affect the results except for one object–the sutra. After you’ve collected the sutra, you can apply it to ward off ghosts and use it to protect yourself from dying or reincarnating into hell. Similar to Tanine Allison’s argument for Until Dawn in her article “Losing Control: Until Dawn as an interactive movie,” the lack of interactivity and player agency in Cosmology of Kyoto are crucial to the meaning of the game. In this game, the players lack the ability to free themselves from reincarnating into hell. The game’s lack of interactivity effectively conveys that humans cannot escape reincarnation without the help of Buddhism and faith. Cosmology of Kyoto is an early example that manipulates the interactivity of gameplay to convey a deeper meaning of the game.

AESTHETIC STYLE

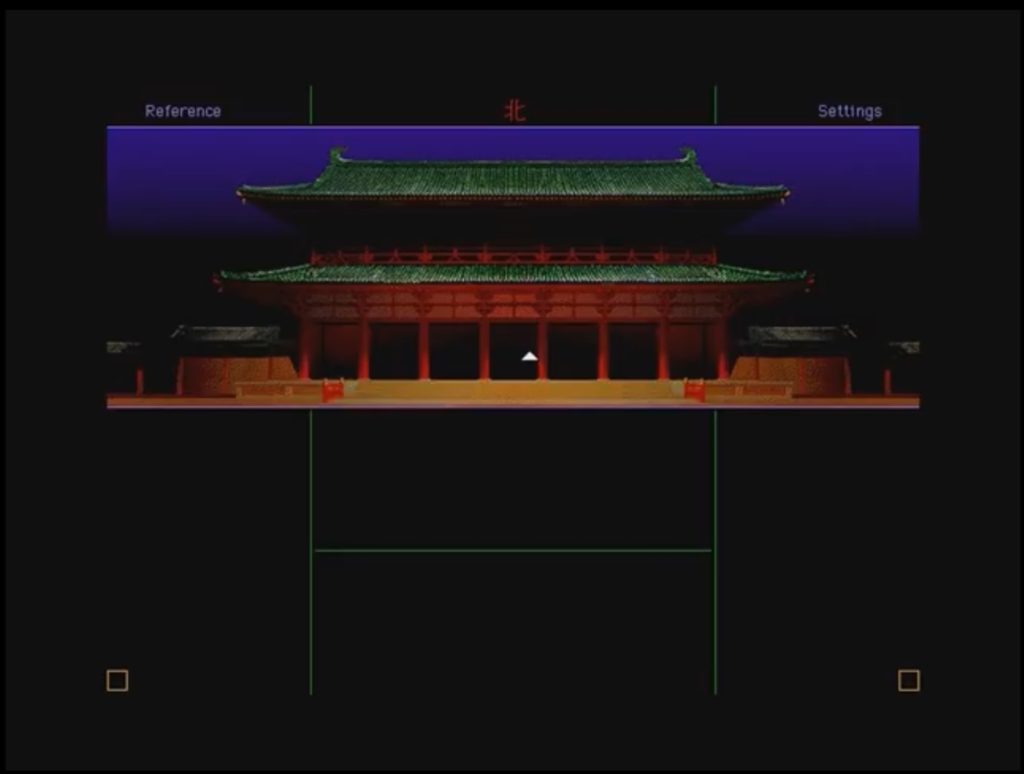

This game is also extremely aesthetic. As mentioned above, the game includes a mixture of traditional and modern art styles. In the human world, the architecture is traditional Japanese style. Many of the scenes are satisfyingly symmetric. Also, what’s really cool is that the frame of the widescreen landscape is in the shape of a traditional Japanese gate.

EDUCATION IN GAMES

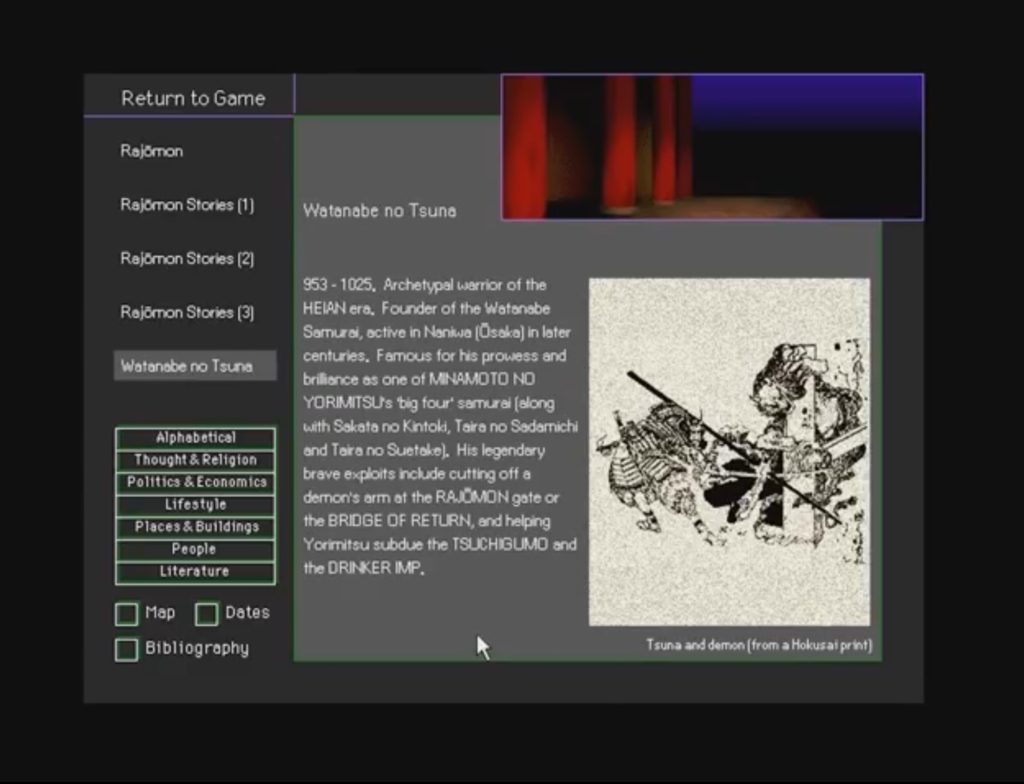

Another contemporary game that I would like to quickly mention is Genshin Impact. Although many other games have this feature as well, one thing I love about Genshin is that it offers pages and pages of background story for each character and just about anything. There’s always a story behind things and it makes the world become much more interesting to explore. Cosmology of Kyoto had this feature. For the majority of people, objects, and places you interact with, there’s a detailed description and background story that you can find in the menu. Most of them are based on real places, real people that existed, or myths that were written by a real person back then. This makes the game fun and engaging despite not having a specific objective, and also allows the player to learn about the history of Kyoto while having fun. As we see today, there are more and more educational games, and many are looking to gamification in education as a way to improve learning.

ORIENTALIST GAME

Japan was undergoing a lot of westernization in the late 20th century, emphasizing on technology and industrialization. Although Spacewar!, arguably the first videogame game, was made at MIT in the United States, Japanese videogames games quickly dominated the videogame industry, from Pac-man to Super Mario Bros, Sonic the Hedgehog to the Legend of Zelda. However, these games, although produced by Japanese game developers, have characters and game worlds designed to fit in western models rather than reflecting traditional Japanese culture. For example, Link and Princess Zelda in The Legend of Zelda are both white and blonde. They have large eyes and long eyelashes that follow Western beauty standards. Cosmology of Tokyo, however, is truly an Orientalist game about traditional Japanese culture and Japanese views on life and death. It is one of the earliest works to use video game as a medium to spread ancient Japanese culture to the world. When I played this game, it reminded me of Pu Songling’s book Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio. They both reflect the traditional Orientalist belief that supernatural things, although undetectable by the eye, do exist, which seem so absurd to the science-oriented western culture. They also both reflect the extreme weirdness and exoticness of Oriental mythologies. Just like how the game itself is a study of Kyoto history, it’s important to study the history of videogames and more specifically, games about ancient asian religion and culture.

DRAWBACKS

One thing to note though is that this game might perpetuate some stereotypes of Orientalism, such as exoticism. Also, the game only focus on certain aspects of Buddhism, such as reincarnation and the importance of the sutras. However, it leaves many other central Buddhist concepts out of the picture, for instance the Four Noble Truths. Thus this video game is not a good representation of Buddhism as a whole, and may end up creating misconceptions about Buddhism.

CORE

Even today, it’s still extremely difficult to develop a game that simultaneously succeeds at being aesthetic, educational, edgy, thought-provoking, fun and engaging. We now have more technology and more money to produce better quality games. However, more recent games made with better technology aren’t necessarily good games. With better technology, it becomes easier for us to get distracted by these fancy technologies or taken away by the more external things. It is important to look back at retro games with relatively simple gameplay and interactive design like Cosmology of Kyoto to remind us that, at the core, a good and successful game does not depend on the technology or tools, but the intentional designs made by the humans behind them.

Works Cited

Article about Japan & videogames: https://www.cnn.com/2017/11/12/asia/future-japan-videogame-landmarks/index.html

Cosmology of Kyoto. Softedge Inc. 1994.

Playthrough video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bGBZg71LncU

Tanine Allison article: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17400309.2020.1787303?casa_token=fFP4mBlzOeoAAAAA%3ALWncwV7Q4AXs_0DRvj03tl8o6P5kcJWQHWsKlrXB-B6S1YAZwwX6v5-4qNni6pjXO0PO1rdL1jkD