In the beginning the Universe was created. This had made many people very angry and was widely regarded as a bad move.

Douglas Adams first published his science fiction cult classic The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy in 1979, telling the story of average British Earthling Arthur Dent as he escapes Earth’s destruction and journeys across a uniquely absurd universe with equally absurd companions as they attempt to discover the meaning of life. If it wasn’t already clear from the short summary, the book is a wonderful piece of absurdist fiction, known for its quirky humour and randomness juxtaposed with the appearance of deep themes such as existentialism, religion, death, as well as others. Characters include an android severely depressed due to his own intelligence. Highly recommend.

However, this post is not about the book The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy published by Pan Books in 1979, but rather the text-based interactive fiction game The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy published by Infocom in 1984, a loose adaptation of the aforementioned work.

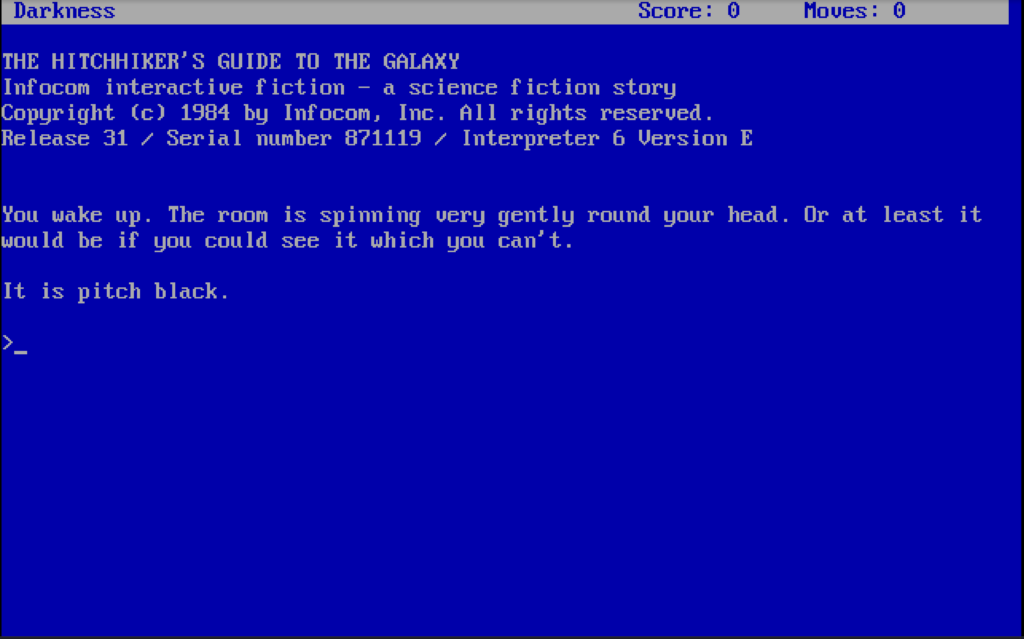

As a loose adaptation, the narrative more or less follows the main events of the book and is split into four parts largely categorised by setting: Earth, Vogon Ship, Heart of Gold, and the Random Scenarios section. As a text-based game, the game controls are fairly straightforward; the player is given a limited amount of action verbs to observe and interact with the game’s world, which is described through text upon the console. What is not straightforward is progression in the game. Let me say now, it is incredibly easy to die.

Thrust into Adams’s world of the absurd, one can no longer rely on one’s fine-tuned and self-developed common sense to figure out what should logically happen next. It did not help that the game made information necessary for progression difficult to find and would punish the player severely (kill them) for any errors they made. Perhaps I’m bad at the game, but I found this game to be ludicrously difficult and did eventually give in to consulting guides to figure out how to progress.

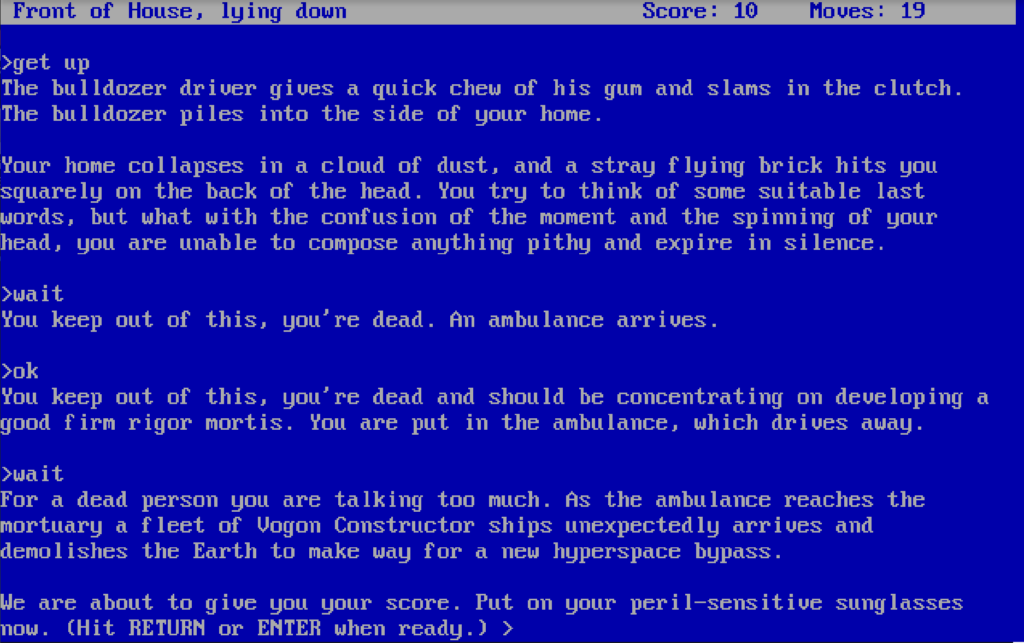

To give an example, spending too long in your room, the first room of the game, will result in death when a bulldozer crashes through your house. Getting up at the wrong time in the path of said bulldozer will also result in death (see above). Taking too long to figure out a puzzle will randomly result in death. Drinking too much beer will result in death. Not eating peanuts will result in death. And so on.

Different parts of the game also require the player to solve devilishly difficult puzzles that are unintuitive and unsolvable if the player does not have all the required items to solve said puzzle, which would be reasonable if the game did not make it impossible to go back to the different settings to retrieve said necessary items. There were many times when I got stuck and had to restore a save, or even restart the game because there was no way to go back in the game. This was in fact a mechanic that was necessary to beat the game, as the final puzzle required an item that could only be found at the beginning of the game, and if you didn’t bring it…

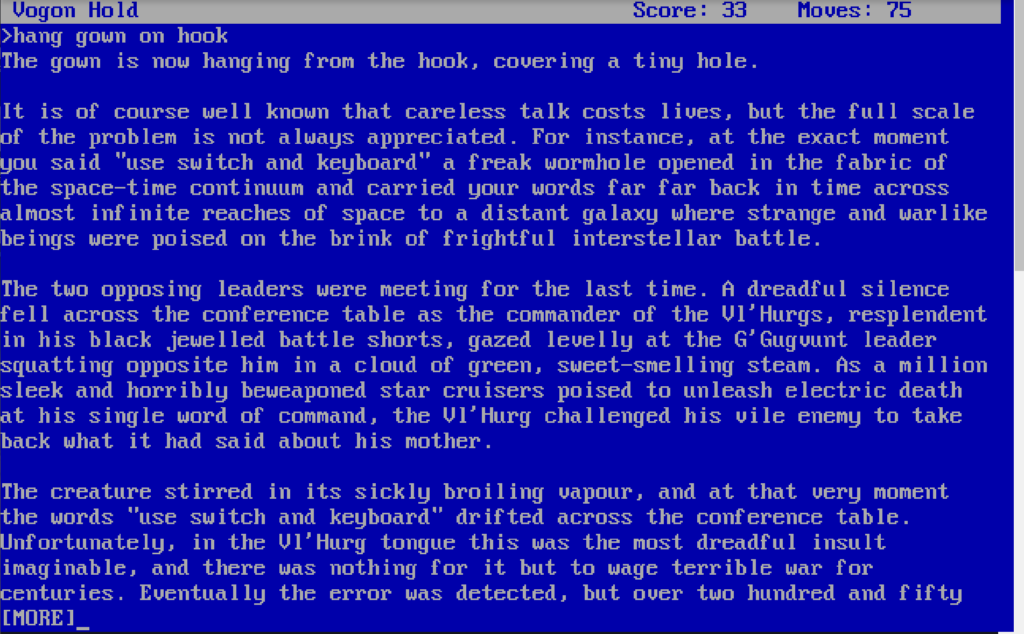

So in short, the gameplay was rather miserable. The only redeeming factor was the comedic writing, and one random event that was the highlight of the game for me (I think it was the fact that I completely expected to be met with another death but instead received this fun little blurb).

I find it a little odd that this is the game to have come out of a work such as The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. For a book that revels in its randomness and absurdity, the game takes away all agency from the player, leaving no room for creativity or playstyles different than what the game prescribes. Trying anything on your own, even entering the wrong sequence of instructions, will either result in death or being stuck. There is only one correct answer, and the game does very little to help you achieve it.

The shortcomings and general “unfunness” could be blamed on the framework of the interaction fiction genre, as it is a more limiting genre than others. Still, it felt less like I was interacting with the fiction, and more like I was playing “guess what I want you to say” with Douglas Adams’s evil clone (except he did write for this game, so it was just him the whole time). This game serves as a wonderful showcase on the frustrating aspects of the genre. Give it a shot if you’d like, but I know I won’t be returning to this game any time soon.