Writing and Humor in The Secret of Monkey Island

The Secret of Monkey Island is a point and click adventure game made by Lucasfilm Games in 1990. In the game, you play as Guybrush Threepwood (why yes, that is a strange name, but everyone’s already told him that), who dreams of becoming a pirate, and must go through certain trials and training to become one, as well as saving the woman he has a crush on from a fearsome pirate. The game consists of puzzles and dialogue options, and while the player can get stuck, the gameplay is forgiving in that you can continue to advance even when you say the wrong thing. The game was constructed so failing through death is close to impossible, and therefore, a large portion of the game is exploration. Even the sword fighting isn’t dangerous, and consists of making decisions on verbal jabs, rather than jabbing with the player’s sword. Hence the focus on narrative.

Dialogue options, and Guybrush’s narration, play a large role in the game. Even though point and click and choosing dialogue are the main mechanics, a lot of the charm is in Guybrush’s remarks or the other characters’ dialogue—even random characters you don’t see or talk to often. Even without voice actors, the intonation and meaning can be gleaned through small snippets of dialogue and expertly placed punctuation.

Very quickly, you can establish Guybrush’s character, and you become endeared with his insight and thoughts on his name, before making it too far into the story. Character is established early on, and this is mirrored with the other characters you meet .Just from one or two lines of dialogue, I can understand what someone is like and what they bring to the story.

Guybrush talks to himself, and in doing so, faces the fourth wall and occasionally directs words to you as the player. Take this moment, for instance, when Guybrush mentions feeling ripped off when he pays for an experience:

Furthermore, humor plays a large role. The insults, for example, while simple, are entertaining, and the way characters interact are charming. Humor is also used to deflect from some of the shortcuts necessary to make the game, such as Guybrush mentioning how amazing it is that the zipline works both ways.

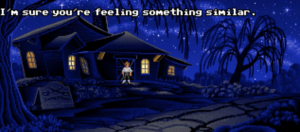

The story is also told environmentally, both though gorgeous backgrounds as well as signs you can inspect or look at. This expands on the world, and a lot of the added details are jokes that fit into the nature of the game. The characters also change appearances occasionally, with flailing arms or changing their clothes to sunbathe for humor. Despite some of the gruesome dialogue or moments (such as cannibals, hanged men, and an intensely animated severed head) the stress is almost always on humor.

It occasionally uses anachronisms to add to the humor (such as a lengthy advertisement when you talk to a pirate who has a “talk to me about Loom” sticker or a dazzling lit up sign for a tourist trap). In these ways, especially with its critique and complacency with advertising, the game has a lasting effect. Even years later, it’s familiar to see this type of critique or straight-out advertisements in a game, and the anachronisms to the pirate age blend it with present day, even with the older pixilated graphics. In fact, the game was remastered in 2009, redone in hand drawn 2D animation. While some view this re-vamp as unnecessary (especially poignant seeing how pixel art continues to be a great and popular medium for games), I think it’s a testament to how charming the game’s writing is to both old and new audiences. As someone who has no nostalgia tied to these types of games, or even the pixel style, I was quickly enchanted (once getting over how difficult it was to use the mouse and dealing with interesting logic of point and click adventure games).

It is easy to see why this game is beloved and was remade. In point and click games today, several of these features are used. Take Little Misfortune, made by Killmonday Games, for example. There’s a heavy focus on narration, and the narrator even talks to you as the player. Little Misfortune’s comments are endearing and cute, and we want to follow her as a character, just as we do with Guybrush.

With the stress on dynamic gameplay, it was refreshing more me, as someone who hasn’t had a deep history of gaming, to see a retro game with a focus on interesting writing, rather than a constant do or die state of gameplay.