Save the Date is a visual-novel-style game wherein the main character attempts to arrange a successful date with Felicia. At first, the player picks between three options for dinner: burgers, Thai food, and tacos. Upon picking any of the paths, the player will soon realize that the date is destined to end in disaster. This is where the quicksave and quickload feature comes in. The player is meant to quicksave at a particular junction in order to explore every possibility. If Felicia ends up dying in one of the paths, the player can load their quicksave and pick a different option. After exploring a handful of different paths, the player might give up on one of the restaurants and try their luck on another.

An interesting aspect of Save the Date is that information learned in one dialogue branch is maintained even after quickloading a different save. As such, exploring paths that lead to a bad end aren’t entirely unproductive, since the player can use information learned from one path in order to obtain new options. In fact, the only way to progress the story past the three restaurants is to learn a secret tidbit about Felicia that causes her to comply when the player says to go elsewhere for their date.

In this description of Save the Date, replacing every instance of the word “player” with “MC” would still make sense. Because of the mechanic where the player retains information, not just externally but also diegetically, it feels like the player and the MC are equivalent characters, or at least there is a much smaller distance between the two entities when playing Save the Date. I felt closer to Felicia than when playing something like Butterfly Soup, because the MC acts as an intermediate that allows me to insert myself into the game. The notion of the diegesis in the game being reality is completely removed. I’m aware I’m playing the game, the MC is aware that they are saving and loading constantly, and Felicia is told that she’s a part of game.

And this meta-awareness by Save the Date is what allows me as the player to become a part of the narrative, rather than a puppet master controlling a narrative by other characters. This is what makes Save the Date different from games where the player can create an avatar. I’m not self-inserting into the MC because I control everything they control. Self-insertion occurs because the MC knows everything that I know, and that any decisions that I make can plausibly be made by the MC as well.

Act 2: Acceptance

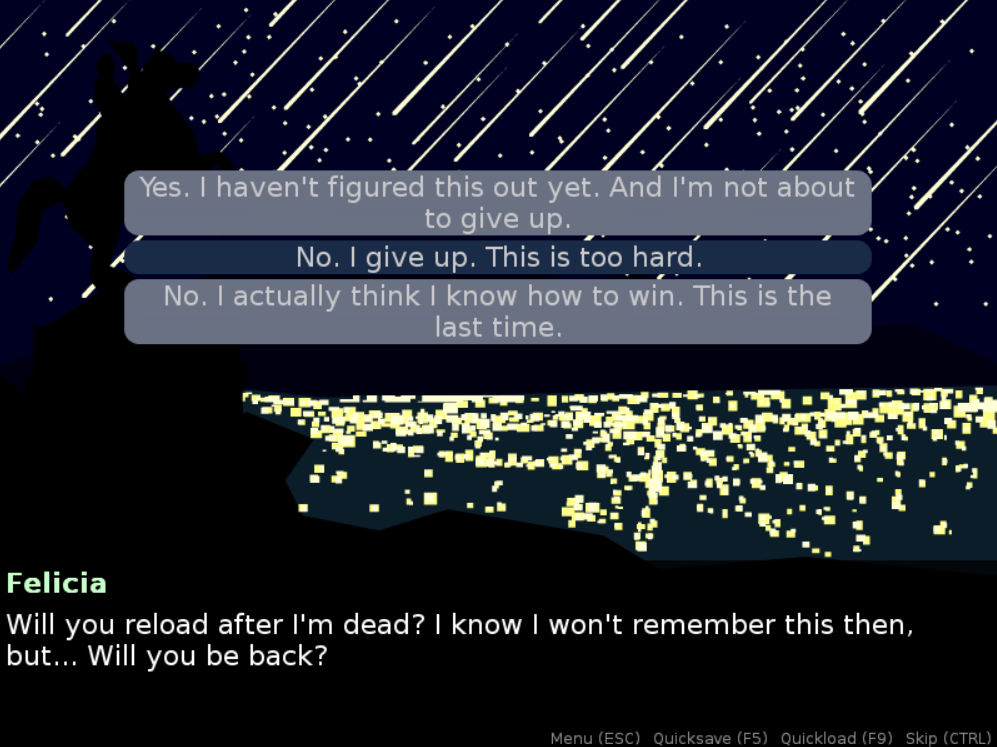

While experimenting with the dialogue choices in what I would call Act 2 of Save the Date, where the MC is with Felicia on the hill overlooking the city, I still had hope that there would be a single branch that would allow me to save Felicia. In the process of exploring all of the dialogue in Act 1, the player takes part in these small moments with Felicia. Moments like when she talks about her dad leaving her when she was six years old, or when she watches the dolphins at the taco place. Assuming the player isn’t mashing through the dialogue, those small moments made me want to believe that this is a character that doesn’t have to die. Eventually, after ~30 bad endings later, I finally accepted the fact that maybe there is no good ending, not in the sense that one can occur by naturally playing the game to the end. I played Act 2 to end one last time, and made the following choice:

And this choice in particular felt bittersweet to me. I wanted to save the date, but I failed. But I also felt content, since I had already accepted this to be the case. Felicia was talking about simply imagining a different ending but it wouldn’t have the same impact. The reason for this might have something to do with how storytelling through games works. The act of choosing the right options to reach a good ending in a visual novel is effort that I had to put into interacting with the game, however small that effort might seem. Defeating a final boss is rewarding not just to attain the ending of the story but in large part to the act of defeating the boss in the first place. Good endings aren’t good endings simply because of their contents, but rather because the player has to get there in the first place. Save the Date embodies this concept, since I had accepted that this is probably the farthest point the game will let me get to on my own, and in a way, this is what I consider to be a “good ending,” or at least an okay ending.

The Hacker Ending

By fiddling with the game files a bit, the player can become a hacker and attain a good ending from the first choice in the game. I’m glad this ending exists, not because I think it is a good ending, but rather because it makes the ending I reached on my own a lot more meaningful. It’s a low effort, abruptly short ending that stands in stark contrast with the ending I reached over the course of many dialogue decisions and playthroughs, and is a great example of how an ending can feel cheap and unfulfilling without the time and gameplay to back it up. Although it could be argued that the hacker ending is a part of the original playthrough(s), I would disagree with that, since it isn’t a choice that arises from information I, and as a result the MC, learned by talking with Felicia. It ruins the close dynamic between the player and the MC that is built through the save and load mechanic, because it’s not me who is trying to go out with Felicia, it’s the MC who is, so a decision that I alone make externally from the game is not a decision that the MC would plausibly make. This further opens up questions about whether the MC feasibly has the power to edit game files, like say Monika from Doki Doki Literature Club, but this blog post is already very long.

I think you’ve made a great point about the player, themself, being a part of Save the Date’s diegetic narrative. I hadn’t thought about how the choice to actually walk away from the game for that last time despite not receiving a traditionally satisfying narrative is actually a diegetic choice, since it is one the game makes explicit reference to. Of course, the game isn’t perfect in making the player a character — interaction is still mediated through predetermined dialogue choices.

I disagree a bit on what the hacker ending meant to me, however. Whenever someone makes a game, especially since the rise of the internet, they have to be aware of the fact that game may be tampered with. I think, to some extent, Save the Date even encourages you to tamper with it, telling the player explicitly to stop playing the game and make their own ending. For many, modding a game is a way to create a new ending. I remember when Mass Effect 3 came out (which, admittedly, I never played) that people were disappointed by the ending and some were spurred to mod in their own “better” version. I think that this kind of tampering is just as valid as something like fanfiction, which is another thing I understood the game as encouraging. I think your point on the separation of the MC and the player is true as far as the first playthrough, but I think as soon as the player realizes that they may be able to save Felicia, the motivations of the MC and the player become one and the same, at least for most players. After all, don’t you want to Save the Date?

On one hand I agree with your idea that sometimes the player and the MC can become one in a meta-game. It’s common for players to enact their own motivations in games, over that of the players, which makes it easy for a Metagames designer to blur the lines between player and main character in the narrative.

That being said, I still think Save the Date, because of its narrative discourages the player from becoming or identifying as the main character. For example, the player does not know who Felicia is, when they begin the game or why Felicia and the MC know eachother, and this is never flushed out during the course of the game (to my knowledge). Also the MC is familiar with the setting of the game, the town, the restaurants, the place where Felicia mentions as her ‘trust’ check. These unknowns keep the player more distant from the MC, who is in fact a character (with a history) that the player only controls for a short amount of time.

Contrast this with the ‘user’ player in There is no Game, and its clear that Save the Date keeps more distance between player and MC than that which is a complete player/character meld. Perhaps this is to suit Save the Date’s narrative and contain the game to the mini-world within and like wise to expand the narrative to that of other genres in There is no game.

I think your conversation of the hacker ending raises several interesting questions, and, ultimately, I think that whether or not it should be considered part of the playthrough depends on your definition of a game or playthrough.

If you believe that a game or playthrough should be more or less self-contained — you run a program, and the game/playthrough exists completely between the start and end of that run — then I think the hacker ending should certainly be considered as a part perhaps separate from the game. On the other hand, if you think that a game or a playthrough can sometimes be extended to include things, mechanics, etc. outside of the game world — if those things are referenced within the game, even if they necessitate quitting the program — then the hacker ending should be considered part of the playthrough.

Personally, I would generally agree with the latter idea. As nielsenth noted in their comment, the player is prompted and encouraged to create their own ending in Save the Date, and altering the game files is one valid way of doing this. I think that once that part of the fourth wall is broken — when the game, or the characters within the game, not only reference the existence of the game but reference the existence of a world separate from it (and, as in this case, when a character explicitly tells the player to “make their own way”) — the playthrough extends beyond just that instance of the program, especially when there is support

I think that this also tracks with the “intention” of the creator, Chris Cornell (not that agreement with authorial intention is entirely necessary). I have no way to verify the identity of the poster on this forum, but, supposedly, the creator of Save the Date posted an explanation of the intended “meaning” of the game: “The theme of the game is ‘Storytelling is cooperative. You, the listener are not a passive content sponge.’ Especially in any sort of game, where the player has any kind of meaningful interaction at all.”

Now, this is definitely a slippery slope that leads us to some complicated questions, given that how much license the player is given to “edit” the game is entirely subjective. If it is true that modding and editing should be considered part of a game (even if those things are implicitly or explicitly mentioned), what is the point at which a game becomes too different from its original version that it should be considered something else?